ブリーフィング

The Sun Also Rises: Towards Japan's "Healthily Functioning Fair M&A Market"

One thing never changes: Japan needs to change. “Change Japan” has been a slogan of Japanese politicians across the spectrum for more than two decades – gradually becoming more background noise than meaningful promise. And all the new foreign investors are in full agreement with the old foreign investors: “Japan Inc.” will be great, just as soon as it turns into something else.

In 2023, both the Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE) and the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) set out to change Japan.

A. The TSE Approach: Shame+Ctrl+F

Roughly 40% of the TSE’s “Prime Market” – the most prestigious (and yet the largest) of the TSE’s three tiers – had a price-to-book ratio (PBR) less than one. In other words, these companies’ market capitalization is less than their apparent liquidation value. This compares with the 10-20% of companies in the same position on the primary markets in the US and Europe.

In March 2023, the TSE addressed a lengthy letter to more than 3,300 listed Japanese companies, urging them to improve PBR and disclose a concrete plan for doing so. This aligns with the TSE’s previously published concerns regarding “the lack of a smooth transition of personnel and capital resources to growing areas”, which inhibits “industrial metabolism and innovation”. Alternative translation: Zombie companies.

The TSE did not set any deadline to improve PBR or take any real-world actions – but for formulating and disclosing plans, the TSE tactic has been a great success. As of 31 January 2024 (see here), the TSE reported that 726 Prime Market companies had published PBR improvement plans. Fast work!

Reading the fine print of the TSE’s list, you will find that it is based on a keyword search, rather than a qualitative review of the disclosures. If a company’s annual corporate governance report contains a section called “Action to Implement Management That Is Conscious of Cost of Capital and Stock Price”, that company is deemed to have satisfied the TSE’s request, regardless of the content.

However, these “concrete plans” vary in just how concrete they are, in how much planning has been done and in how (if at all) they will be put in practice. As of July 2023, roughly half of the disclosed plans refer to an initiative to “review the business portfolio” (i.e., consider divestitures), compared to >80% of participating companies planning on “investment for growth”. “Sustainability initiatives”, “enhancement of governance” and “strengthening of IR” are also popular and equally valid as “concrete plans” to improve PBR.

B. The METI Approach: Guidance

In August 2023, METI made its own effort to “correct” the root causes of stagnation in the Japanese economy – it published “Guidelines for Corporate Takeovers” (the 2023 Guidelines). These follow on from METI’s narrower “Takeover Defense Guidelines” (2005), “MBO Guidelines” (2007) as amended and replaced by “Fair M&A Guidelines” (2019) as a non-binding framework of best practices for Japan-listed companies to follow in corporate transactions.

The METI group that drafted the 2023 Guidelines was formed in 2022 “with the objective of encouraging acquisitions that are favorable for the economy and society to occur in a healthily functioning fair M&A market”. You may wince at the reference to “society” as a stakeholder – giving target management a society-sized excuse to entrench itself. But when closely examined, the 2023 Guidelines are more rigorous than previous METI guidance – at least that is METI’s intention.

For example, contrary to the usual Japanese style, the 2023 Guidelines clearly set out actual ‘dos and don’ts’ for listed Japanese companies facing corporate takeover offers. There is even direct reference to directors’ duties of care and loyalty with an emphasis on each independent director`s responsibility– a warning that “by referring to and acting based on the best practices presented in the Guidelines, the risk of breaching the duty of care and duty of loyalty of directors will be reduced…”.

For Japan, this is pretty strong stuff! METI does not quite say that failing to follow the 2023 Guidelines amounts to a fiduciary duty breach – but does lay out a path for (activist) shareholders and (unsolicited) bidders to make that argument.

C. What changes after the 2023 Guidelines?

The typical “playbook” of Japanese target management, when receiving an unsolicited offer, has been extremely difficult to overcome. The 2023 Guidelines recommend against several of these typical practices, in an effort to stimulate a more dynamic M&A environment. That being said, at a first glance of the 2023 Guidelines, you may find it disappointing, continuing to emphasize “corporate value” (rather than share price) and stakeholders (rather than shareholders) as the primary constituency. But if you read them carefully and, in particular, together with “Public Comments”, you can see METI has moved away from a traditional Japanese understanding of vague, subjective, stakeholder capitalist “corporate value”.

The 2023 Guidelines attempt to address all of these issues with the following:

1. An offer should be taken to the board of directors (rather than ignored). The 2023 Guidelines indicate that all takeover offers should be reported to the board of directors (including disclosure to at least one independent, non-executive director) so that directors can assess whether further steps are warranted.

2. The board should sincerely consider the offer and whether it is “bona fide”. The 2023 Guidelines list various factors for a board to consider in evaluating the good faith of an offer. To the extent that these focus on the “specificity” and “feasibility” of the offer (to use the 2023 Guidelines terminology), these make sense from the international perspective – a board need not waste much time on an offer that does not delineate price or other key terms, or that is effectively impossible due to financing or regulatory risks.

However, the 2023 Guidelines’ “bona fide” concept also incorporates the target’s analysis of the offer’s “rationale of purpose”. Target directors need not “sincerely consider” an offer if they:

a. are not able to review and evaluate the bidder’s business strategy for the post-closing period; or

b. believe that the offer is made for the purpose of obtaining confidential or competitively sensitive information, without an intention to complete a deal.

METI does warn Japanese targets not to arbitrarily interpret the meaning of “bona fide offer”, and suggests that outside directors lacking M&A expertise should engage professional advisors to assess an offer’s good faith.

3. The offer should not be rejected on the grounds of employee job security. While the 2023 Guidelines’ discussion (not to say, definition) of the term “corporate value” remains complex, multifarious and potentially problematic, METI annotated what “corporate value” really means in its Public Comments. As METI noted, the 2023 Guidelines “clearly” state that “corporate value” is “conceptually the sum of the present values of discounted future cash flows generated by a company” equal to “the sum of shareholder value (market capitalization, from the market perspective) and net debt value” equal to “a company’s assets, profitability, stability, efficiency, growth potential, and other company attributes that contribute to the interests of shareholders, or the extent to which they do so”. METI also warns that the corporate value concept should not be “used as a tool for management to defend themselves” including “management referring to retention of employees as an excuse”.

It’s unfortunate that METI didn’t express its intention unequivocally in the 2023 Guidelines themselves, but buried it in the Public Comments. However, this tactic is not unusual when the government really wants to change something under various stakeholders' pressures. So, a core principle of the 2023 Guidelines as annotated by METI’s accompanying Public Comments is that the board should not turn down an offer which would enhance a company’s “corporate value”, which is the shareholder value.

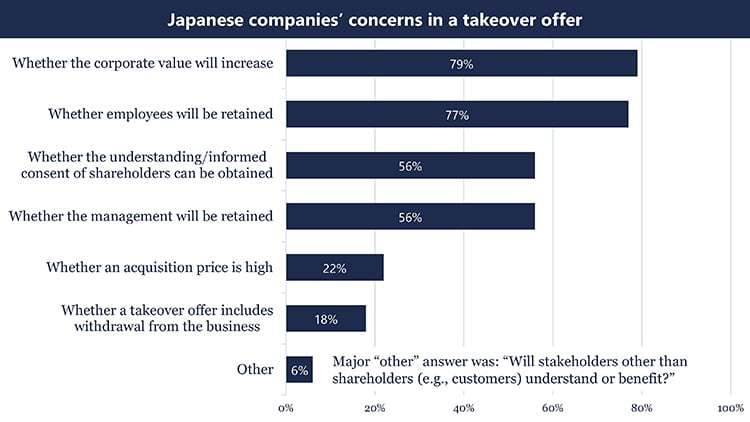

(Source) Prepared based on Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry’s survey to companies listed on the First and Second Sections of the Tokyo Stock Exchange (FY2020 survey).

※Note that the term "corporate value” in this chart is that of pre-2023 Guidelines encompassing various stakeholders interests.

4. Targets should not bombard offerors with questions. Japanese takeover defenses – whether through formal “advance warning plan” poison pills or informal responses to unsolicited offers – typically involve detailed discussions of the potential acquiror’s post-closing plans for the corporation and its businesses.

The 2023 Guidelines attempt to curtail this tactic, stressing that limiting opportunities for due diligence and asking overly detailed questions of the offeror as a precondition to engaging in the due diligence process should not be used as tactics to prevent the acquisition of control.

More broadly, the 2023 Guidelines refer to the fair treatment of offers in due diligence processes. Unlike in certain European jurisdictions, Japan does not require that rival bidders be afforded equal access to diligence information, and unsolicited bidders in Japan have rarely had any access to non-public information. Nevertheless, in guiding boards to engage with offers that may ultimately be value-enhancing, METI puts a thumb on the scale in favor of providing diligence access in parallel with a bidder’s development of a “bona fide” offer and post-closing strategy.

5. Outside directors should take more responsibility. Less than 17% of TSE’s Prime Market companies have a majority of outside directors. So, for 83% of the most prestigious Japanese public companies, the board’s ability to supervise management is questionable.

The 2023 Guidelines include a general recommendation that companies without a majority independent board, in considering a takeover offer, should set up a majority-independent special committee. This extends a previous METI recommendation in the MBO context (see our note – here) to a much wider range of potential corporate transactions.

The 2023 Guidelines further encourage public disclosure “on how each outside director fulfilled their supervisory functions” to facilitate decisions “on the subsequent director selection and dismissal”. The effect is to justify outside directors who actively challenge insiders during the evaluation of offers, as activists may target outside directors and allege failures to act in accordance with the 2023 Guidelines.

D. What comes next?

In 2023, the TSE and METI made significant efforts to stimulate a more vibrant “industrial metabolism”. In 2024, we will begin to understand whether these efforts have been successful. Despite the flaws in the TSE’s PBR disclosure requirements and METI’s 2023 Guidelines, early indications are positive:

1. Investment majors’ move to oppose the reappointment of “Presidents” of PBR below 1. Two major investment management firms, Mitsubishi UFJ Asset Management Co., Ltd. and Nissay Asset Management Corporation, will vote against the reappointment of a representative director of a PBR-below-1x-Japanese company, including President Shacho – the most senior figure in an organization – from April 2027 and June 2025 respectively. Those that fail to follow TSE’s PBR disclosure requirements could be sanctioned earlier than 2027, Mitsubishi noted.

2. The “MBO Rush”. A record-high volume of MBO take-private transactions over the past 12 months may indicate that low PBR companies are responding to pressures from the TSE. In addition to high ongoing listing costs, and the new PBR-improvement plan disclosure requirements, the TSE intends over time to rationalize the disproportionate number of listed companies on the highest-prestige Prime Market. Companies with high founder family shareholders, PBR below 1.5 and/or stagnating growth (e.g., in the technology context) are most likely to reconsider the benefits of being listed in Japan.

Less certain is whether these MBOs will follow METI’s recommended practices, and how the TSE’s efforts will interact with METI’s previous MBO guidelines. A recent MBO offer for Taisho Pharmaceutical Holdings Co Ltd has been fiercely criticized by shareholders based on both price (representing a PBR of 0.85, so significantly less than break-up value even after a >50% premium was added to share price) and process (the effectiveness of the special committee). This offer succeeded thanks to the support of founder family shareholdings (c. 40%), but shareholders may petition the court to determine a fair squeeze-out price in the forthcoming squeeze-out process.

3. The NIDEC experience. Although the 2023 Guidelines appear far from perfect from the international perspective, they have already been cited as a key factor in at least one successful unsolicited bid.

NIDEC Corporation in 2008 made an unsuccessful unsolicited offer to Toyo Denki Seizo K.K., which was abandoned in the face of a barrage of public questions from target management. However, in its second attempt to acquire TAKISAWA Machine Tool Co., NIDEC’s offer letter made 15 separate references to the (then draft) 2023 Guidelines, and trumpeted its compliance with METI’s recommendations. The bid succeeded and TAKISAWA’s CEO later told the Nikkei that there was no option other than to agree, if TAKISAWA was to comply with the 2023 Guidelines. Targets in other circumstances may be able to take a more assertive view over time (as has happened with other METI Guidelines as they are digested by the market) – but early indications, including Dai-ichi Life’s win against a preceding M3’s friendly offer to Benefit One, are positive.

4. Takeover by analogy: application to carve-out disposals. One way to improve PBR is to sell underperforming and non-core assets – and in the face of TSE pressure and increasing shareholder activism, many TSE-listed companies are considering such sales. If the 2023 Guidelines can be conceived of as akin to US Revlon duties (with Japanese characteristics), then there is a question of when a potential carve-out constitutes the abandonment of a long-term strategy and “break-up” of the company (which in the US could trigger a Revlon duty to, in sum, hold an auction). The 2023 Guidelines do not on their face apply in the context of carve-outs and business disposals, but may organically affect the background expectations of shareholders (as well as directors and courts) as to how corporate transactions should be conducted. Exciting times!

By Tomoko Nakajima, with thanks to Noah Carr